Process Flow and Basic Principle Analysis of Reversible Cold Rolling Mill

In the intricate landscape of modern metallurgy, the production of high-strength, precision-gauge, and superior-surface-finish metal strip is a testament to engineering prowess. At the heart of this capability for many specialty steel and non-ferrous metal producers lies the reversible cold rolling mill. Unlike its continuous tandem mill counterparts designed for massive volumes of a single product, the reversing cold rolling mill offers unparalleled flexibility, making it the equipment of choice for processing smaller batches, high-value alloys, and products requiring exacting mechanical properties. Understanding the fundamental principles that govern its operation and the meticulous flow of material through its system is essential to appreciating its role in advanced manufacturing. This analysis delves into the core mechanics and the detailed process journey within a cold reversing mill, highlighting the critical interplay of force, friction, and control.

The Fundamental Principle of Plastic Deformation in a Reversing Rolling Mill

The foundational principle of any cold rolling process, including the reversing cold mill, is the permanent plastic deformation of metal through compressive stress. The mill accomplishes this by feeding a strip of metal, known as the feedstock, through the narrow gap between two counter-rotating cylinders called work rolls. This gap, precisely set smaller than the incoming strip's thickness, forces the material to elongate and reduce in cross-section. The seemingly simple act of squeezing metal belies a complex internal mechanism. As the metal is compressed, its grains are stretched and fractured, leading to strain hardening or work hardening, where the material becomes stronger and harder but less ductile. This is a defining characteristic of the cold rolling process. The immense forces required for this deformation—often reaching thousands of tonnes—generate significant heat through internal friction and must be meticulously managed. The reversible cold rolling mill uniquely performs this reduction not in a single, continuous forward pass, but in a series of sequential passes back and forth over the same set of rolls, allowing for precise intermediate control and adjustment. The ability to reverse the direction of strip travel is what grants this mill its name and its strategic flexibility.

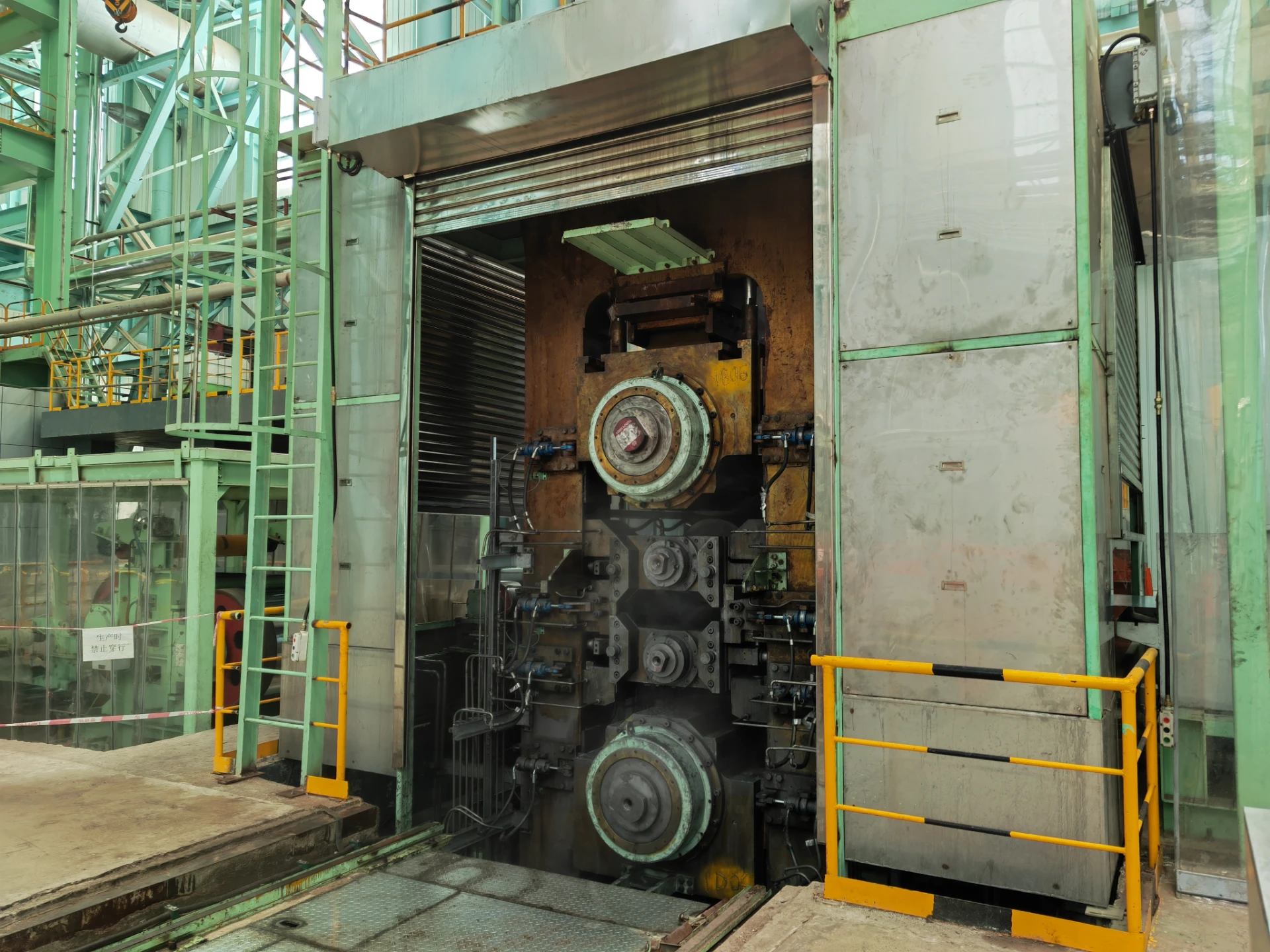

Anatomy of a Modern Mill: From 4-Hi to 6-Hi Configurations

The architecture of the mill stand itself is a direct response to the challenges of applying and containing these colossal forces. The most basic design, the 2-high mill (two work rolls), is insufficient for most cold rolling applications due to excessive roll deflection under load, which would produce a strip that is thicker in the middle and thinner at the edges (a phenomenon known as crown). To combat this, modern mills employ cluster configurations.

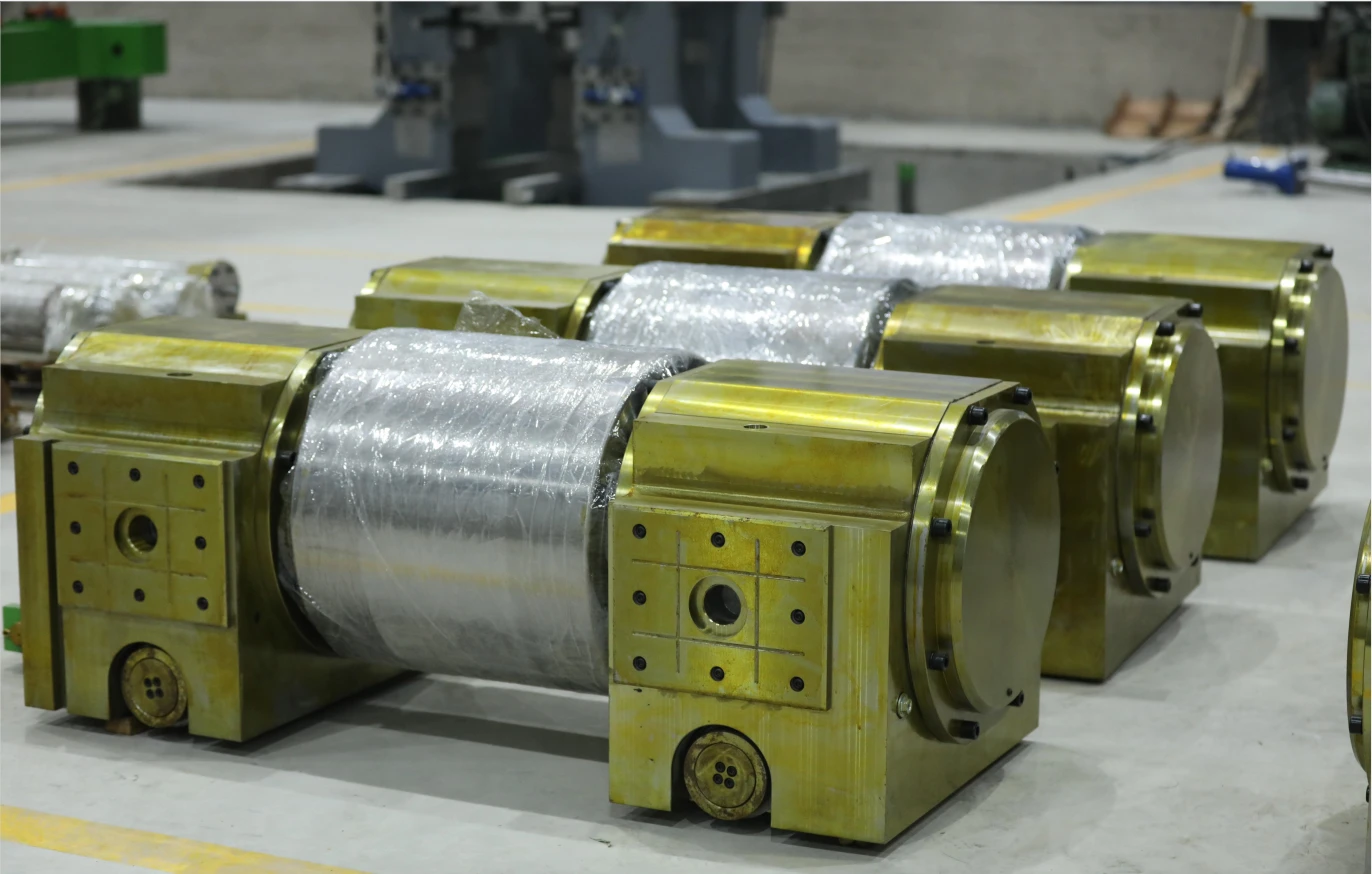

The 4hi reversible cold rolling mill introduces a pair of larger, robust backup rolls behind the smaller work rolls. The primary function of these backup rolls is to provide rigid support to the work rolls, drastically reducing their bending and ensuring a consistent gap profile across the entire strip width. This design is robust, relatively simple to maintain, and highly effective for a wide range of products and widths, making it one of the most common configurations in the industry.

For even more demanding applications, particularly involving very high strip tensions or extremely hard materials, the 6 hi reversing cold rolling mill offers a superior solution. This design incorporates a third set of rolls—the intermediate rolls—positioned between the work rolls and the backup rolls. The intermediate rolls can often be axially shifted (moved sideways). This feature provides operators with an additional powerful tool to control the roll gap's shape and, consequently, the strip's cross-sectional profile and flatness. It allows for more precise manipulation of the pressure distribution across the roll barrel, enabling the rolling of thinner gauges with exceptional uniformity. The choice between a 4-hi and a 6-hi reversible cold rolling mill is a strategic decision based on the product mix, quality requirements, and capital investment considerations.

The Detailed Process Flow of a Cold Reversing Mill

The journey of a coil through a reversing rolling mill is a carefully choreographed sequence of events, blending mechanical handling with precision metallurgical transformation.

Preparation and Loading: The process begins with a hot-rolled and pickled coil, which has been annealed to restore ductility after the hot rolling process. This coil is transported to the mill entry area, where it is loaded onto the payoff reel. The leading end of the coil is mechanically prepared, often by shearing to create a square edge that can be cleanly fed into the roll bite.

Threading and Initial Pass: The operator, or an automated system, feeds the prepared strip head through the mill guides, into the pinch rolls, and finally through the work rolls of the mill stand. This initial threading is a critical step. Once through, the head is secured into the tension reel on the opposite side. With the strip now anchored at both ends by the payoff and tension reels, the first rolling pass can commence. The mill is set to a specific roll gap and speed, and the strip is drawn through the stand, undergoing its first reduction in thickness.

The Reversing Cycle: Upon completing the first pass, the strip is fully wound onto the entry-side tension reel. This is where the "reversing" action occurs. The mill drive system decelerates, stops, and then accelerates in the opposite direction. The roles of the reels switch: the tension reel becomes the payoff reel, and the payoff reel becomes the tension reel. The strip is then drawn back through the stand for a second pass, often with a smaller roll gap to achieve a further reduction. This back-and-forth cycle is repeated multiple times, with the strip becoming longer and thinner with each pass.

In-Process Control and Annealing: A key advantage of this process is the ability to monitor and control the product after each pass. Gauge meters continuously measure thickness, and shape rollers assess flatness. The mill operator or an automated control system can adjust roll bending, lubrication, or tension between passes to correct any deviations. For some very hard grades, the strain hardening may become so severe that an intermediate anneal is required partway through the schedule. The coil is removed from the mill and placed in a furnace to recrystallize the grains and restore ductility before being returned to the mill to complete its reduction.

Unloading and Finishing: Once the final target thickness and mechanical properties are achieved, the coil is unloaded from the tension reel. It is then typically sent for a final continuous annealing or batch annealing process to soften it to the desired temper, followed by skin passing (a very light final roll) to impart the required surface finish and flatness before final inspection and shipping.

Reversing Rolling Mill: Interplay of Speed, Tension, and Lubrication

The operation of a reversible cold rolling mill is not merely about reduction. It is a symphony of precisely coordinated control parameters. Strip tension, applied by the reels, is paramount. It helps pull the strip through the roll bite, reduces the required rolling force, and is a primary tool for maintaining flatness and preventing slippage or breaks. Rolling speed must be carefully ramped up and down to manage inertia and ensure stability during the critical reversal phases. Lubrication and cooling are equally vital; a specialized emulsion is flooded onto the rolls and strip to reduce friction, carry away the immense heat generated, and ensure a high-quality surface finish. In a modern mill, a computer-based control system integrates all these variables—force, tension, speed, and geometry—using mathematical models to execute an optimal rolling schedule with minimal human intervention.

In conclusion, the reversible cold rolling mill represents a perfect marriage of fundamental physical principles and sophisticated control engineering. Its process flow, centered on the strategic reversing pass sequence, provides a level of operational flexibility and product quality control that is indispensable for the metals industry. From the robust 4hi reversible cold rolling mill to the advanced 6 hi reversing cold rolling mill, the continuous evolution of this technology ensures its place as a critical tool in manufacturing the high-performance materials that underpin modern technology and infrastructure.

-

YWLX’s 1450mm Six-Hi Reversing Mill Goes Live in BangladeshNewsNov.24,2025

-

Adjusting Roll Gap in 6Hi Reversing Cold Rolling Mill for Thin StripNewsNov.13,2025

-

Quality Control Standards for Automatic Gauge Control in Strip RollingNewsNov.13,2025

-

Effect of Skin Pass Rolling on Metal DuctilityNewsNov.13,2025

-

Key Components of a Modern TempermillNewsNov.13,2025

-

Common Wear Patterns of Work Roll in Tandem Cold Mill OperationsNewsNov.13,2025

-

Revolutionary Skin Pass Rolling Technology for Enhanced Steel QualityNewsNov.04,2025